Market volatility can be a complex subject, but understanding a few basic principles can help you implement strategies to capitalize on volatility extremes.

Volatility-based trading approaches have traditionally been popular among hedge funds, commodity trading advisors, and other professional traders. There are many ways to gauge volatility and incorporate it in a trading strategy. Of the different ways to characterize and trade volatility, the best are based on the tendency of volatility to “revert to the mean.”

The premise behind volatility mean reversion is that periods of extraordinarily high volatility should be followed by periods of lower, more normalized volatility. Similarly, periods of extraordinary low volatility should be followed by periods of higher, more normalized volatility. This tendency is reflected by the familiar progression of a market that meanders in a narrow trading range (a low-volatility condition), only to explode out of the consolidation and embark on a strong price trend (a highvolatility condition). Eventually, the price move exhausts itself, at which point volatility will again fall to a lower level.

We’ll analyze the two simple methods for trading volatility in the forex market: inside days and shortterm/ long-term volatility comparisons.

Consecutive inside bars

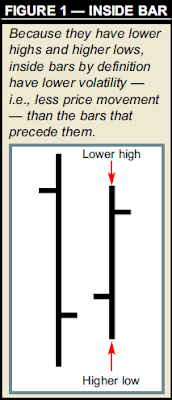

An inside bar is a bar whose range is contained within the prior bar’s range — that is, the bar’s high and low do not exceed the previous bar’s high and low (see Figure 1). They are easy to identify visually and should be one of the basic patterns traders should notice immediately.

An inside bar is a bar whose range is contained within the prior bar’s range — that is, the bar’s high and low do not exceed the previous bar’s high and low (see Figure 1). They are easy to identify visually and should be one of the basic patterns traders should notice immediately.Inside bars by definition have lower volatility — that is, less price movement — than their preceding bars, and successive inside bars reflect progressively shrinking volatility. Per the mean-reversion theory, the more inside bars, the higher likelihood of a volatility surge or a breakout scenario.

The following volatility trade can be implemented after at least two consecutive inside bars have formed. This type of strategy is best employed on daily charts; the longer the time frame, the more significant the potential breakout.

The strategy works for both longs or shorts. Although entry orders can be placed on both sides of the market, traders should use other tools to determine the bias for a particular trade. For example, if the inside days occur within a bullish chart pattern, such as a developing ascending triangle, this increases the likelihood of an upside breakout. On the other hand, if the inside days are developing within a descending triangle formation, this increases the likelihood of a downside breakout. Here are the rules for a long trade setup:

1. Buy above the high of the most recent inside bar.

2. Place a stop-and-reverse (SAR) order a few pips (approximately 5 to 10 pips, depending on the bid-ask spread) below the low of the most recent inside bar. The purpose of the SAR order is to reverse the position if the initial move turns out to be a false breakout.

3. If the position moves higher by the risk amount (the difference between the entry price and the stop price), sell half the position and replace the SAR order with a trailing stop.

4. If the SAR order is triggered after the entry, place a stop a few pips above the high of the most recent inside bar.

Short trades: For a short trade, the rules are the same except that you enter below the low of the most recent inside day and place an SAR order a few pips above the high of the most recent inside day.

Figure 2 shows two consecutive inside bars in the U.S. dollar/Canadian dollar (USD/CAD) rate. Applying the strategy, a buy order is placed above the high of the most recent inside bar, while a stop is placed below the low of the most recent inside bar. The long order is triggered and a 200-pip rally ensues with virtually no retracement.

Figure 2 shows two consecutive inside bars in the U.S. dollar/Canadian dollar (USD/CAD) rate. Applying the strategy, a buy order is placed above the high of the most recent inside bar, while a stop is placed below the low of the most recent inside bar. The long order is triggered and a 200-pip rally ensues with virtually no retracement. Figure 3 shows a more complex trade example in which the SAR order is triggered. Because of the bullish implications of the ascending triangle that was forming when the two inside bars appeared, the long-trade entry rules were executed:

Figure 3 shows a more complex trade example in which the SAR order is triggered. Because of the bullish implications of the ascending triangle that was forming when the two inside bars appeared, the long-trade entry rules were executed:1. We placed an order to go long a few pips above the high (.7660) of the most recent inside day. The order was triggered.

2. We placed an SAR order a few pips below the low of the most recent inside day at .7600 for a risk of approximately 60 pips. The SAR was triggered when the market broke out of the bottom of the triangle, and we sold the original long position and entered into a new short position.

3. When the market moved lower by the risk amount (60 pips), we sold half the position (at .7540). We then used a 30-pip trailing stop on the remaining position.

The low on April 14, 2004 was .7299, and we exited the remaining half of the position at .7329.

Volatility comparison

Currency option volatilities measure the rate and magnitude of the past and potential future changes in a currency’s price, and they can be a useful tool for timing currency movements.

Implied option volatilities, which are reflected in option premiums, are the market’s current estimate of the future fluctuation of a currency’s price. Historical (or statistical) volatility, which reflects past price movement, is typically measured by calculating the annualized standard deviation of price changes over a given period (e.g., 20 days, 100 days).

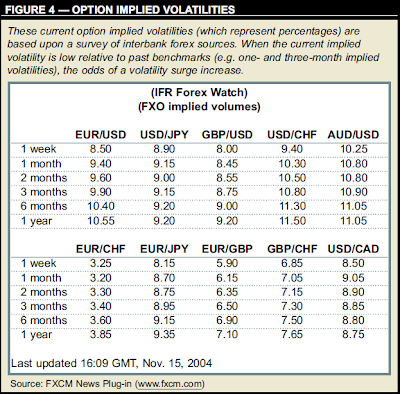

Figure 4 shows only current option implied volatilities (which are based upon a survey of interbank sources). Traders implementing this strategy would need to keep a journal tracking historical implied volatilities. Onemonth and three-month implied volatilities are two of the most commonly benchmarked time frames.

Figure 4 shows only current option implied volatilities (which are based upon a survey of interbank sources). Traders implementing this strategy would need to keep a journal tracking historical implied volatilities. Onemonth and three-month implied volatilities are two of the most commonly benchmarked time frames.When option volatilities are low, traders should look for potential breakouts. Current implied volatility should be at least 25 percent lower than historical implied volatility. (It is best to measure against actual historical volatility, but that data is not always readily available.) Conversely, when option volatilities are high, traders should look for range trading opportunities.

Typically, when a currency trades in a range, its option volatility will decline, because by definition range trading means lack of movement.

When option volatilities make a pronounced down move, it is usually a sign of a significant potential price move and upcoming trade opportunity.

This characteristic is very important for both range and breakout traders.

Traders who usually sell at the tops of ranges and buy at the bottoms can use this approach to predict when their strategy could potentially stop working, because if volatility becomes very low, the likelihood of continued range trading decreases.

On the other hand, breakout traders can monitor option volatilities to make sure that they are not buying or selling into false breakouts. If volatility is at average levels, the likelihood of a false breakout increases. Alternatively, if volatility is very low, the probability of a real breakout is higher. However, traders must be careful because volatilities can have long downward trends, as they did between June and October 2002. Therefore, declining volatilities can sometimes be misleading. What traders need to look for is a sharp move in volatility, rather than a gradual one.

Figure 5 shows an example in the U.S. dollar/Swiss franc rate (USD/CHF). The blue line is price, the green line is the one-month (or shortterm) volatility, and the red line is three-month (or longer-term) volatility. For most of December 2003 the onemonth volatility was below the threemonth volatility, which coincided with the development of sharp down moves in USD/CHF. Between Feb. 24, 2004 and March 9, 2004, the one-month volatility spiked above the threemonth volatility, which coincided with a period of range trading.

Figure 5 shows an example in the U.S. dollar/Swiss franc rate (USD/CHF). The blue line is price, the green line is the one-month (or shortterm) volatility, and the red line is three-month (or longer-term) volatility. For most of December 2003 the onemonth volatility was below the threemonth volatility, which coincided with the development of sharp down moves in USD/CHF. Between Feb. 24, 2004 and March 9, 2004, the one-month volatility spiked above the threemonth volatility, which coincided with a period of range trading.All shapes and sizes

Volatility is expressed many ways — on different time frames and in term of option prices and past price fluctuations in an underlying market.

Understanding some simple volatility principles, such as mean reversion, can help you time trades when a volatility shift is likely to occur.

0 comments:

Post a Comment